മലയാളികളുടെ കുടിയേറ്റ ജീവിതത്തിൽ ഇന്നു് ലോകത്തിന്റെ തന്നെ മിടിപ്പുണ്ടു്. ഭൂമിയിൽ എവിടെയും അവളുണ്ടു് എന്നു് മാത്രമല്ല, മനുഷ്യാനുഭവത്തിന്റെ ഏതു് സന്ദർഭങ്ങളിലും അവൾ ചെന്നു പെടുന്നു. യുദ്ധങ്ങളിൽ അവൾ അഭയാർത്ഥിയാവുന്നു, വിപത്തുകളിൽ അവൾ ഇരയാകുന്നു, ഇപ്പോൾ ഈ മഹാമാരിയുടെ കാലത്തും. അമേരിക്കയിലെ തന്റെ ലോക്ഡൌൺ ജീവിതത്തെ ഒരു ഫോട്ടോ എസ്സേയിലൂടെ പകർത്തുകയാണു് കവിയും പ്രബന്ധകാരിയുമായ ആർദ്രാ മാനസി. ലേഖനത്തിന്റെ ഇംഗ്ലീഷ് മൂലവും മലയാള പരിഭാഷയുമാണു് ഇന്നു് സായാഹ്ന പ്രസിദ്ധീകരിയ്ക്കുന്നതു്.

സായാഹ്നപ്രവർത്തകർ

ഡിസംബർ അവസാനവാരങ്ങളാവുമ്പോഴേയ്ക്കും വല്ലാത്തൊരു ഭീതി എന്നിൽ ഉറഞ്ഞുകൂടാറുണ്ടു്. ഹേമന്തത്തിന്റെ തീക്ഷ്ണവും ദയാരഹിതവുമായ തണുപ്പു്. ജീവനില്ലാത്ത ഇരുണ്ട ആകാശങ്ങൾ. എന്റെ അപ്പാർട്ടുമെന്റിനു താഴെ എന്നോ നിശ്ചലമായ തെരുവു്. ഒപ്പം എന്നിൽ പൂർത്തികരിക്കാത്തതും പൂർണ്ണമാകാത്തതുമായ അഭിലാഷങ്ങളുടെ ഒരു വർഷം കൊഴിയുന്നതിന്റെ നൊമ്പരങ്ങളും.

ഇവിടെ, ഞാൻ താമസിക്കുന്ന ന്യൂയോർക്കിൽ ഉച്ചയ്ക്കുശേഷം നാലുമണിയാകുമ്പോഴേ ഇരുളുവാൻ തുടങ്ങും. ദിവസം അവസാനിക്കാൻ പോകുന്നു എന്ന തോന്നലാണു് അതുളവാക്കുന്നതു്. അപ്പോൾ എന്റെ മനസ്സും ശരീരവും താനേ ഉൾവലിയാൻ തുടങ്ങുന്നു. എല്ലായ്പ്പോഴുമെന്നപോലെ അപ്പോഴൊക്കെ ഞാൻ എന്നോടുതന്നെ പറയാറുണ്ടു് വസന്തം അകലെയല്ലെന്നു്. സുഗന്ധവാഹിയായ, ദീർഘമായ പകലുകളുടെ, തെരുവിൽ ആഹ്ലാദം നിറഞ്ഞ കലപില ശബ്ദങ്ങളുള്ള, ജാലകത്തിൽ സൂര്യവെളിച്ചം നിറയ്ക്കുന്ന വസന്തം. കഴിഞ്ഞ ഡിസംബറിലും ഞാനിതുതന്നെയാണു് എന്നോടു പറഞ്ഞുവച്ചതു് പിന്നെ 2020 സമാഗതമായി. എന്റെ പ്രതീക്ഷയിലെ ന്യൂയോർക്ക് വസന്തമാകട്ടെ ഇരുൾഗർത്തത്തിലാണ്ടുപോയി. ചുറ്റും മരണവും, രോഗവും യാതനകളുമൊക്കെയായി മഹാമാരിയുടെ വിളയാട്ടമായിരുന്നു.

മാർച്ചിന്റെ തുടക്കം മുതൽ ഞാൻ വീടിനുള്ളിൽ തന്നെയായിരുന്നു. പുതിയ യാഥാർത്ഥ്യത്തോടിണങ്ങിച്ചേരുവാൻ ഞാൻ നന്നേ പാടുപെട്ടു. ഒരു മുറിയിൽ നിന്നും മറ്റു മുറികളിലേയ്ക്കു നടക്കുക മാത്രമായിരുന്നു എനിക്കു് ചെയ്യാനുണ്ടായിരുന്നതു്! ഈ നടത്തത്തിൽ വാതിലുകളും ഫർണിച്ചറുകളും മാത്രമായിരുന്നു ഞാനറിഞ്ഞിരുന്നതു് ആസന്ന വർത്തമാനകാലവുമായി എന്നെ ബന്ധപ്പെടുത്തുന്നതു് അവ മാത്രമാണെന്നു തോന്നി.

ദിവസവും വൈകിട്ട് ഏഴുമണിയാകുമ്പോൾ ജനാലപ്പടിയിലേയ്ക്കു ഞാൻ ഓടിയെത്തും. അപ്പോഴാണു് എന്റെ തൊട്ടയൽക്കാരെയും തെരുവിനെതിർവശത്തുള്ള അപ്പാർട്ടുമെന്റിലുള്ളവരെയും കാണുന്നതു് നഗരത്തിന്റെ ജീവൻ നിലനിർത്തുവാൻ സ്വന്തം ജീവിതംപോലും മറന്നുപ്രവർത്തിക്കുന്ന ആരോഗ്യപ്രവർത്തകരെയും മറ്റവശ്യസേവനത്തിലേർപ്പെട്ടവരേയും ഞങ്ങൾ കൈകൊട്ടിയും പാത്രങ്ങൾ കൊട്ടിയും ഓർമ്മിച്ചു. ക്രമേണ ഇതു ഞങ്ങളുടെ ദിനചര്യയായിത്തന്നെ മാറിക്കഴിഞ്ഞു. യഥാർത്ഥത്തിൽ ഞങ്ങളുടെ ഉത്കണ്ഠകളും ആഘാതങ്ങളും ഉച്ചാടനം ചെയ്യുവാനുള്ള ഒരനുഷ്ഠാനം കൂടിയായിരുന്നു ഇതു്.

എനിക്കു വന്ന ഒരു ഓഫീസ് ഫോണിനിടെ എന്റെ സ്നേഹിത അവളുടെ ട്രക്ക് ഡ്രൈവറായ സഹോദരന്റെ ട്രക്ക് ശീതികരണി ഘടിപ്പിച്ചു് സഞ്ചരിക്കുന്ന ശവഗേഹമാക്കിയ വിവരം പറഞ്ഞു. നഗരത്തിലെ ശവഗേഹങ്ങളൊക്കെ മരിച്ചവരെക്കൊണ്ടു നിറഞ്ഞിരിക്കണം. മരണത്തെ ഇപ്പോഴും അതിജീവിക്കുന്നതിൽ ചിലപ്പോഴെങ്കിലും നിസ്സഹായതയാലും കുറ്റബോധത്താലും ഞാൻ വീർപ്പുമുട്ടി. മറ്റു ചിലപ്പോൾ സ്വയം അപ്രത്യക്ഷയാകുവാൻ ഞാനൊരിടം തേടി. ഈ ക്രൂരമായ ലോകത്തെ മറികടന്നു് മറ്റൊരു ലോകത്തെത്തുവാൻ ഞാനാഗ്രഹിച്ചു. മെല്ലെയാണു് ഞാനാഗ്രഹിച്ച ലോകം കവിതയുടേതാണെന്നു് വിസ്മയത്തോടെ ഞാൻ തിരിച്ചറിഞ്ഞതു്. സന്ദേഹങ്ങളേതുമില്ലാതെ കവിത എന്നെ സ്വീകരിക്കുമെന്നുറപ്പുണ്ടായിരുന്നു.

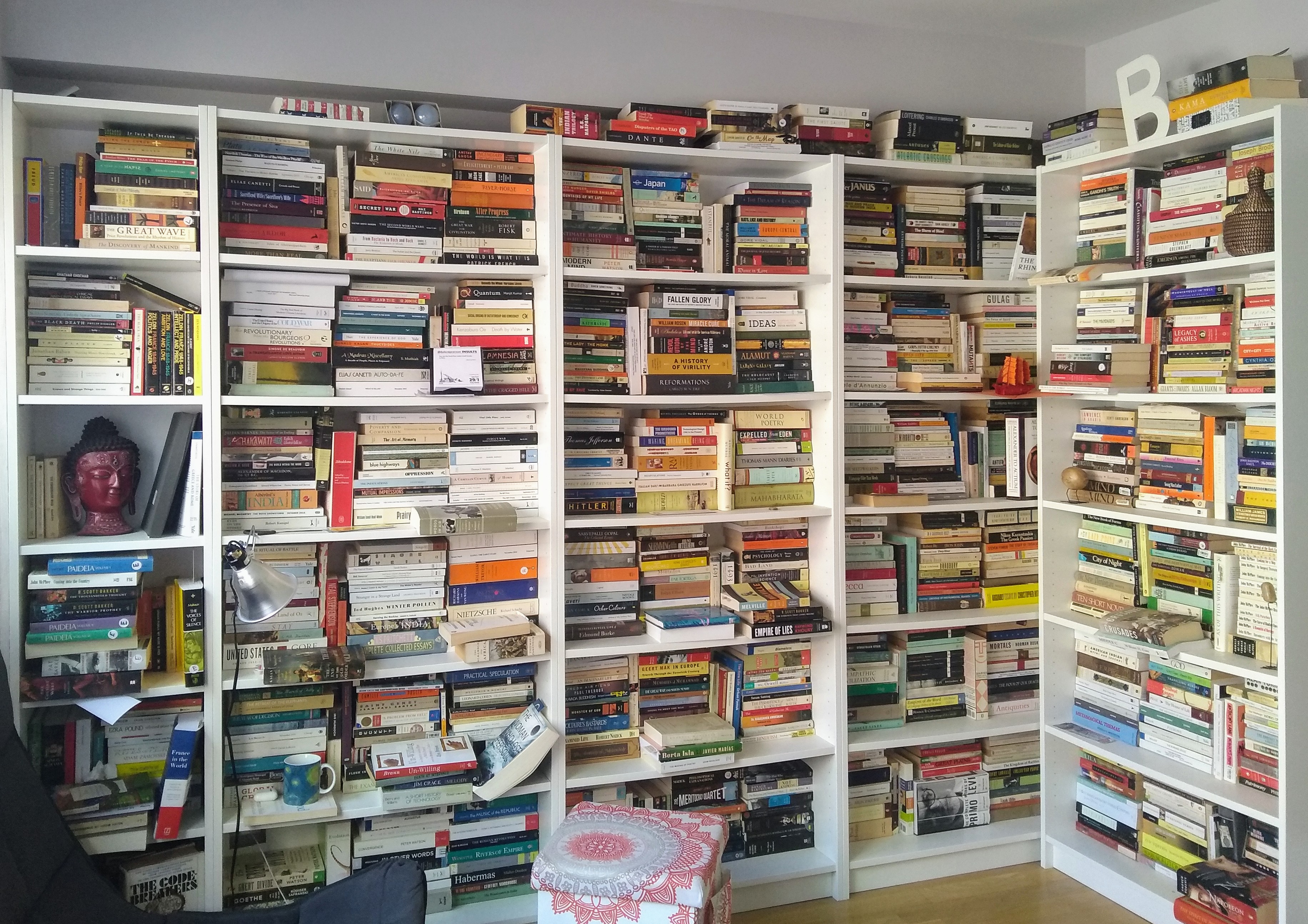

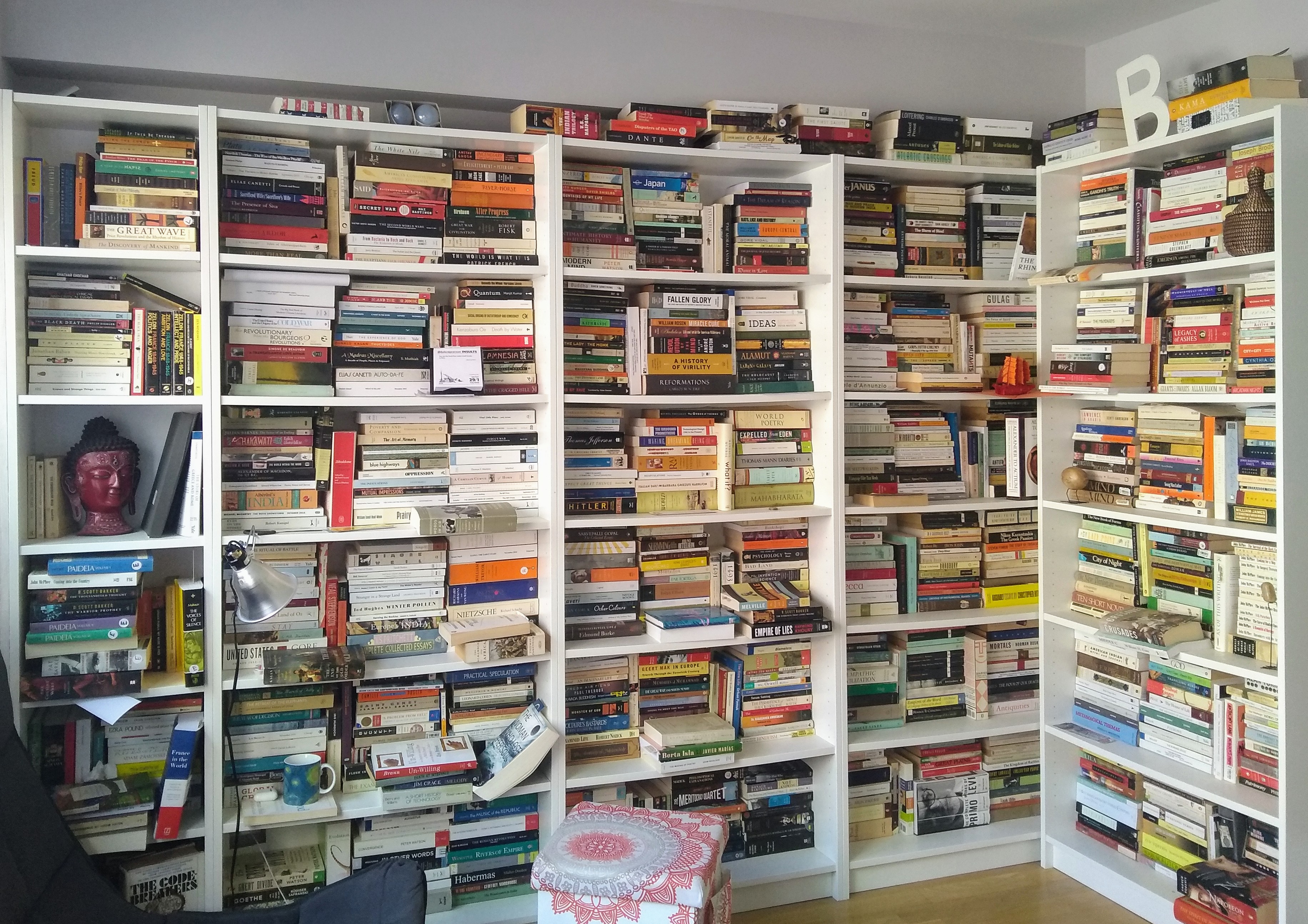

എത്രയോ ആഴ്ചകൾ തുടർച്ചയായി ലോക കവിതകളുടെ ഭാഷാന്തരങ്ങൾ ഞാൻ വായിക്കുകയായിരുന്നു! കൊറിയൻ, ഇന്ത്യൻ, ചൈനീസ്, ജാപ്പനീസ്, യൂറോപ്യൻ, അമേരിക്കൻ എല്ലാം. ഈ സാഹചര്യത്തിൽ നിന്നും തങ്ങളിൽ നിന്നു തന്നെയും ആദേശം ചെയ്യപ്പെട്ടതായ തോന്നലുകൾ പുലർത്തുന്ന ധാരാളം മനുഷ്യരുണ്ടെന്നു് എനിക്കറിയാം. ഞാൻ അന്നു വായിച്ച കവിതകൾ മിക്കപ്പോഴും പേരുകളില്ലാത്ത നമ്മുടെ വികാരങ്ങളോടും വിസ്മയങ്ങളോടും തന്നെയാണു് സംവദിച്ചിരുന്നതു്.

കുറെ വർഷങ്ങൾക്കുമുൻപു് ന്യൂയോർക്കിൽ എത്തിയ നാൾ മുതൽ ഇവിടുത്തെ ബ്രൂക്ക്ലിൻ ബൊട്ടാണിക്കൽ ഗാർഡനിൽ വർഷംതോറും ഏപ്രിലിൽ കൊണ്ടാടുന്ന “സക്കുറ മറ്റ്സുറി’ എന്ന ജാപ്പനീസ് ചെറി ബ്ലോസം ഫെസ്റ്റിവലിൽ പങ്കെടുക്കണമെന്നു് തീവ്രമായി ആഗ്രഹിച്ചിരുന്നു. പല കാരണങ്ങൾ കൊണ്ടും അതു നടന്നില്ല. ആ നിരാശയെ മാറ്റി നിർത്തിക്കൊണ്ടു് ഇക്കുറി ഞാനെന്റെ ജാലകത്തിലൂടെ “കാലറി പെയർ” വൃക്ഷത്തിൽ സൂര്യൻ അടിമുടി സഞ്ചരിക്കുന്നതു നോക്കിനിന്നു. മാർച്ച് മദ്ധ്യത്തോടെ അതു മഞ്ഞിന്റെ നിറമുള്ള വെള്ളപ്പൂക്കൾ ദേഹമാസകലം ചൂടിനിന്നു. സക്കുറ മറ്റ്സുറി എനിക്കുവേണ്ടി ജാലകത്തിലൂടെ വിരുന്നു വന്നതായിരിക്കണം അതെന്നു ഞാനെന്നെ വിശ്വസിപ്പിച്ചു. കഴിഞ്ഞ മാർച്ച് പതിനഞ്ചിനായിരുന്നു ആ കാഴ്ച ഞാൻ കണ്ടതു് അന്നു ഞാൻ ചൈനീസ് കവി ചാങ് യു (1333–1385)വിന്റെ കവിത വീണ്ടും വായിച്ചു. ഹേമന്തത്തിലെ തിളങ്ങുന്ന പൂക്കളെ നോക്കി കവി തന്റെ ‘സുഗന്ധത്തെ കേൾക്കാനുള്ള പവിലിയൻ’ എന്ന കവിതയിൽ ഇങ്ങനെ കുറിച്ചു.

“മറ്റുള്ളവർ അവയെ പലകുറി

മണത്തുനോക്കാമെന്നു് പ്രതീക്ഷിക്കുന്നു.

പക്ഷേ, എന്റെ കർണ്ണപുടങ്ങളെ

കൂട്ടുപിടിക്കാനാണെനിക്കിഷ്ടം.

സുഗന്ധം രത്നതുല്യമായ ഗാനങ്ങളുതിർക്കുന്നു.

അവ ഉച്ചത്തിൽ പാടുമ്പോൾ

എന്റെ ആഹ്ലാദത്തിനതിരില്ല.

ശബ്ദത്തിനു സുഗന്ധമില്ലെന്നു്

ആരാണു് പറഞ്ഞതു്?”

(ഇംഗ്ലീഷ് ഭാഷാന്തരം: ജൊനാതൻ ചാവ്സ്)

വിചിത്രമായ വഴികളുള്ള ഇന്ദ്രിയങ്ങളെക്കുറിച്ചാണു് കവിത പറയുന്നതു്—കാണാനുള്ളവയെ കേൾക്കാൻ കഴിയുന്നതിനേയും, കേൾക്കാനുള്ളവയെ കാണാൻ കഴിയുന്നതിനെയും കുറിച്ചു്. സന്തോഷത്തിന്റെ മറ്റൊരു തുരുത്തിലെത്തിയതായി എനിക്കുതോന്നി. വർത്തമാനകാലത്തിന്റെ ഉദ്വിഗ്നതകളെ രേഖപ്പെടുത്തുവാൻ ഞാനൊരു പുതിയ മാർഗ്ഗം കണ്ടെത്തുകയായിരുന്നിരിക്കണം. ഞാൻ സങ്കൽപ്പിക്കാൻ തുടങ്ങി. ഏതാനും ആഴ്ചകൾക്കപ്പുറം തളിരിട്ട ചില്ലകളിൽ കുരുന്നിലകളുമായി നിൽക്കുന്ന കാലറി പെയറിലെ ശ്വേതപുഷ്പങ്ങൾ തെരുവിൽ പരവതാനി വിരിച്ച വേനലിനു സ്വാഗതമോതും. അപ്പോൾ സൂര്യൻ കത്തിജ്ജ്വലിക്കുകയായിരിക്കാം. പിന്നെയും ഒരാഴ്ചയ്ക്കുശേഷം മാർച്ച് 22 മുതൽ ഋതുസംക്രമണങ്ങളെ വ്യാഖ്യാനിക്കുവാനും മനസ്സിൽ തോന്നിയതൊക്കെ പ്രകടിപ്പിക്കുന്നതിനുമായി ഞാൻ ട്വിറ്ററിൽ ഒരു കവിതാപംക്തി ആരംഭിച്ചു. ‘ക്വാറന്റൈൻ വരികൾ’ എന്ന ഹാഷ്ടാഗിൽ ഓരോ ദിവസവും ഓരോ കവിത പങ്കുവെച്ചു. അത്ഭുതമെന്നോണം ഞാൻ 100 കവിതകൾ പൂർത്തിയാക്കി!

“ ദിനംതോറുമുള്ള ഈ വരികൾ കാലത്തെ പിന്തുടരുവാനുള്ള കൌതുകകരമായ ഒരു മാന്ത്രികച്ചരടാണു്” ഒരു സുഹൃത്തു് ട്വിറ്ററിൽ കുറിച്ചു.

ദിവസവുമുള്ള ഈ വ്യായാമം ജാലകത്തിനപ്പുറത്തു് മാറിമറിയുന്ന ഋതുക്കളെ ഓർമ്മിപ്പിച്ചുകൊണ്ടേയിരുന്നു.

“ നിങ്ങൾ പഴകി ജീർണ്ണിച്ച ഒരു വീടിനെപ്പോലെയുണ്ടു്”ചീകിയൊതുക്കാത്ത എന്റെ തലമുടിയും തളർന്ന ഭാവവും കണ്ടു് എന്റെ ഭർത്താവു് തമാശയെന്നോണം പറഞ്ഞു.

“അടിച്ചേല്പിക്കപ്പെട്ട ഈ ക്വാറന്റൈൻ കൊണ്ടു് അങ്കഗണിത രീതിയിലല്ല, മറിച്ച് ക്ഷേത്രഗണിത രീതിയിലാണു് ഞാൻ വയസ്സായിക്കൊണ്ടിരിക്കുന്നതു്” മറുപടിയായി ഞാൻ പറഞ്ഞു. ഹെയ്ൻ (794–1185) കാലഘട്ടത്തിലെ ജാപ്പാനീസ് കവി ഓനോ കൊമാച്ചിയുടെ കവിത ഞാനോർമ്മിച്ചു.

“പൂവിന്റെ നിറങ്ങൾ മങ്ങി,

നിർത്താതെ പെയ്യുന്ന മഴപോലെ,

ചിന്തകളിൽ നഷ്ടപ്പെട്ട പോലെ,

ഞാൻ വയസ്സായിക്കൊണ്ടിരിക്കുന്നു.”

(ഇംഗ്ലീഷ് ഭാഷാന്തരം: കെന്നത്ത് റെക്സ്റോത്ത്)

ഈ മഹാമാരിയ്ക്കിടയിൽ അപ്രത്യക്ഷമാകുന്ന നമ്മുടെ ജീവിതങ്ങളുടെ സത്തയെ കൊമാച്ചി വാറ്റിയെടുത്തതെങ്ങനെയെന്നു ഞാനത്ഭുതപ്പെട്ടു. ജീവിതം പൊടുന്നനെ ദുർബ്ബലവും ക്ഷണികവുമായിത്തീർന്നതുപോലെ. അപ്രതീക്ഷിതമായി സർവ്വവും ശിഥിലമാകുമ്പോൽ നാം തമ്മിൽ നിന്നു തന്നെയോ, ബാഹ്യലോകത്തുനിന്നോ ഉത്തരങ്ങൾ തേടുമെന്നു ഞാൻ മനസ്സിലാക്കി. കൊമാച്ചിയുടെ കവിതകൾ വ്യാപകമായി ഭാഷാന്തരം നടത്തിയിട്ടുള്ള ജെയിൻ ഹർഷ് ഫീൽഡ് എഴുതുന്നു, “കവിത നമ്മെ നമ്മിലേയ്ക്കു തന്നെ നയിക്കുന്നു, ഒപ്പം നമ്മിൽ നിന്നു് അകലേയ്ക്കും”.

പുറത്തെ അടയാളങ്ങൾക്കായി ഞാൻ ജാലകത്തിലൂടെ സൂക്ഷ്മമായി നിരീക്ഷിക്കാൻ തുടങ്ങി. മാസങ്ങൾ കടന്നുപോകവേ, ജാലകവിരികളുടെ മറ നീക്കിയപ്പോൾ വെളിയിലെ ചാറ്റൽ മഴയുടെ ഗന്ധം എനിക്കനുഭവപ്പെട്ടു. കിളികളുടെ ശബ്ദങ്ങൾ കേട്ടുതുടങ്ങി. ഒരു ദിവസം ഒരു ചുവന്ന ജേ പക്ഷി ജാലകത്തിനു കോണോടുകോണായി പറക്കുന്നതു ഞാൻ കണ്ടു. പറവയെ ശ്രദ്ധിച്ചുകൊണ്ടിരുന്നപ്പോൾ വസന്തം മെല്ലെ നിശ്ശബ്ദമായി പിൻവാങ്ങി. ഞാനെന്നോടുതന്നെ പറഞ്ഞു, വൈകാതെ ഒരിയ്ക്കൽ കൂടി ഹേമന്തം ഇവിടെയെത്തും.

(ഇംഗ്ലീഷിൽ നിന്നു വിവർത്തനം: മേഘ്ന)

By the last weeks of December, I usually find that a certain dread begins to take shape within me. Outside, the winter cold is harsh and unrelenting, the skies are lifeless and dark and the street on which my apartment stands has long gone silent. Alongside, the despair of another year gone by reminds me of unfulfilled and unfinished promises to myself. In New York where I live, it begins to go dark by four-thirty in the afternoon. It feels as if the day has come to an end. And my mind and body begin to withdraw and pause. Then, every so often, I tell myself that spring can’t be far. Spring with its fragrances, long days, happy chatter in the streets and sunlight that floods my windows. This is what I told myself last December. But then, 2020 arrived. What followed in New York during the months of spring this year were some of the darkest months, with death and misery in many corners due to the pandemic.

Since early March, I have stayed indoors and struggled to make sense of this new reality. I walked from one room to another, trying to feel the doors and furniture—as if they were the only signs that tethered me to my immediate present. At 7 PM every day, I rushed to the window to join my neighbors (and others across the city) who showed up at their windows—as we clapped our hands and banged utensils to remember the sacrifice of health workers and other essential workers who risked their lives to keep the city alive. This had become a part of our lives—a daily ritual and an exorcism of our anxieties and traumas. During an office call, a colleague shared with us how her brother who was a driver had to convert his truck into a refrigerated “mobile morgue”. The city’s mortuaries had run out of space for its dead. On occasions, I felt helpless and guilty, for the mere act of surviving. On others, I longed for a place to disappear, to simply sidestep this world that I found myself in. Slowly, poetry became that place which would take me in without questions.

For weeks on end, I read world poetry through translations—Korean, Indian, Chinese, Japanese, European and American. Like me, I knew there were people who felt displaced from this moment and, perhaps, from themselves too. The language of the poems I read, on occasion, spoke to emotions and wonders for which we did not have names. Since first arriving in New York some years ago, I have wanted to go see the Sakura Matsuri in April—the annual Japanese cherry blossom festival—at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden. For one or the other reasons, that has never happened. This year, putting aside that disappointment, I watched the sun travel down the Callery Pear tree outside my window. In the middle of March, the tree burst with its snow-white blossoms. The Sakura must be here, I thought. To mark that day, March 15th, I reread a poem by the Chinese poet Chang Yu (1333–1385). Looking at the “bright flowers of the cold season”, Yu writes in his poem ‘The Pavilion For Listening to Fragrances’.

“Others are hoping to smell them a few times,

but I prefer to use my ears!

The fragrance sends forth jewel—like songs;

singing them aloud, I feel such joy!

And who says there is no fragrance in sound?”

(Translated by Jonathan Chaves.)

The poem speaks about senses in unexpected ways—hearing things that you can see and seeing things that you can hear. I felt a great sense of happiness, as if I had found a new way of registering the present. As I stood at the window, I imagined how in few weeks, the white blooms of the Callery Pear will carpet the streets and will make way for summer, with its green shoots, tender leaves, and a fierce sun.

A week later, on March 22nd, in an effort to annotate this change of seasons and all that I felt within, I started a personal project where I posted one poem a day on Twitter with the hashtag #QuarantineVerses. Through some minor miracle, I completed posting 100 poems. “Your daily journal of verses is an interesting way of tracking time”, a friend wrote to me on Twitter. This daily exercise was a way to remind myself of the changing seasons outside my window. My husband joked that I had begun to look like a “decrepit building”, with my unkempt hair and a sense of ennui. I told him that I was aging geometrically across this self-imposed quarantine and not arithmetically. I remembered reading Ono no Komachi from the Japanese Heian period (794–1185) who wrote,

“The colors of the flower fade

as the long rains fall,

as lost in thought,

I grow older.”

(Translated by Kenneth Rexroth.)

I was struck by how Komachi distilled the essence of our vanishing lives amidst this pandemic. Life suddenly was colored by fragility and transience. When things fall apart, I realized we seek answers within ourselves and, to my surprise, as well as in the world outside. Jane Hirshfield, who has extensively translated Komachi, writes: “Poetry leads us into the self, but also away from it”.

I began to start looking more carefully, for signs outside my window. As the months passed, when I moved my windows curtains, I could almost smell the light rain. I could hear the birds. And one day, I spotted a red Jay fly diagonally across my window. As I watched the bird, spring began to retreat, quietly. And, before long, I told myself, winter will be here once more.

ന്യൂയോർക്കിൽ താമസം. യു. എസ്., യു. കെ., ഇന്ത്യ തുടങ്ങിയ രാജ്യങ്ങളിൽ ആനുകാലികങ്ങളിലും സമാഹാരങ്ങളിലും കവിതകൾ പ്രസിദ്ധീകരിച്ചിട്ടുണ്ടു്. 2020-ൽ ഒരു അന്താരാഷ്ട്ര ഓൺലൈൻ എക്സിബിഷനായ IGNITE—From Within the Confines”-ൽ തന്റെ കൃതികൾ പ്രകാശിപ്പിച്ചുകൊണ്ടു് കലാകാരന്മാരുടേയും കവികളുടേയും ചിന്തകളെ COVID-19 എന്ന പകർച്ചവ്യാധിയുടെ നേർക്കു് തിരിച്ചുവിടാൻ ആർദ്രയ്ക്കു് കഴിഞ്ഞു. റട്ജേഴ്സ് യൂണിവേഴ്സിറ്റിയിലെ ‘സെന്റർ ഫോർ വിമൻസ് ഗ്ലോബൽ ലീഡർഷിപ്പ്’ (CWGL)-ൽ പ്രവർത്തിയ്ക്കുന്നു.