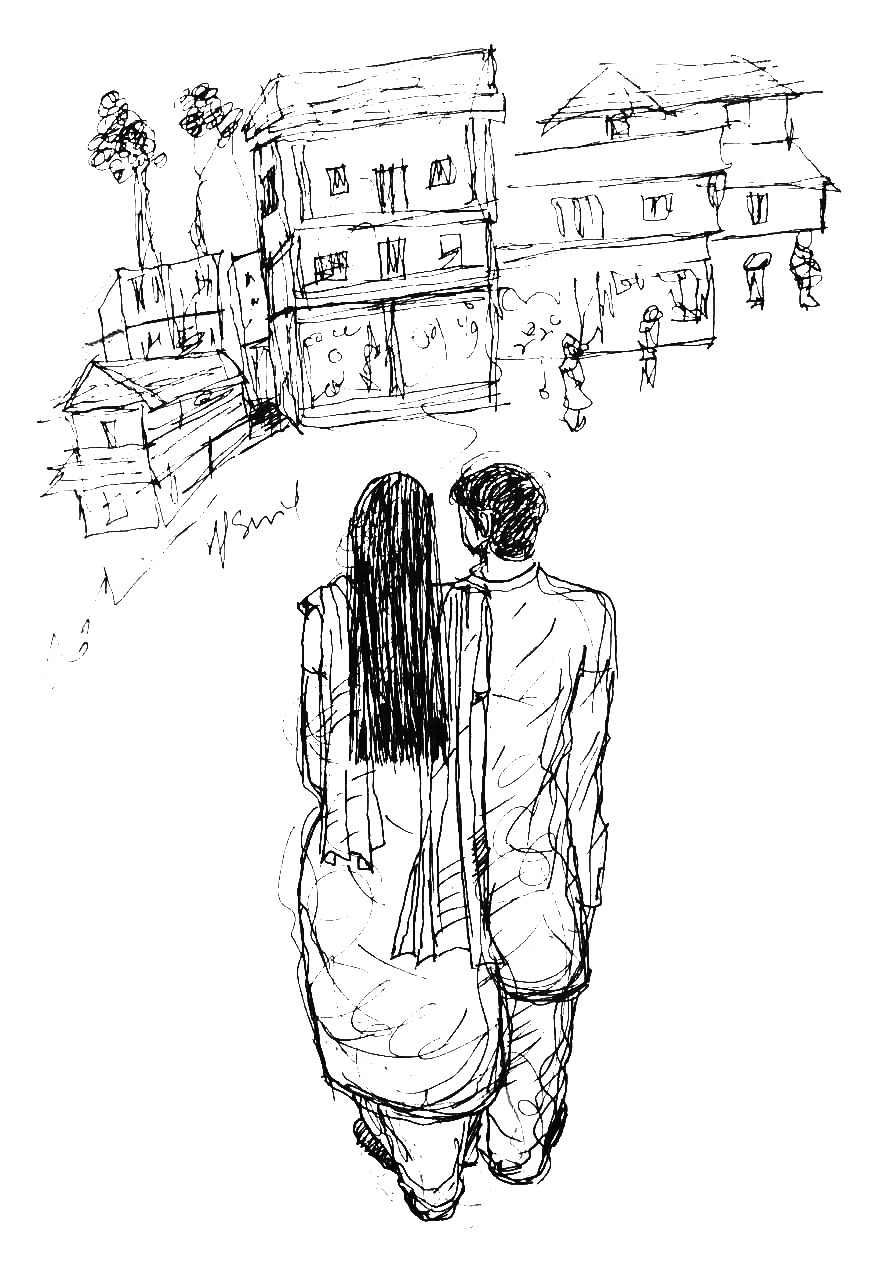

When Chandralekha came to meet Minar, there boomed in his drawing room a dominating din from the protest rally–fourth in the day–passing down the street, so Minar could not hear clearly what she was saying. During the days which followed, the little of what she said got submerged in the memory of that procession and noise. Saying “I did not hear whatever you said,” Minar moved to the bedroom away from the din taking her along. Before that he shut the balcony door which was kept open to view the procession.

Chandralekha hesitated at the bedroom door. Looking at her Minar laughed and said, “My friend, presently this is the bedroom of a man and woman who live a geriatric life!” Bharati, Minar’s wife drew a chair and placed it close to the bed. She invited Chandralekha into the room, saying “We have met once.” Minar sat on the bed facing Chandralekha. Street is now on the window side. He asked Bharati to prepare two cups of tea, “Be sure to make a special tea for Chandralekha. Along with my fee she used to buy special tea for me!” Chandralekha laughed turning to Bharati. Minar mulled over his age and that of the guest sitting across to him. Chandralekha had asked his age once, he recalled.

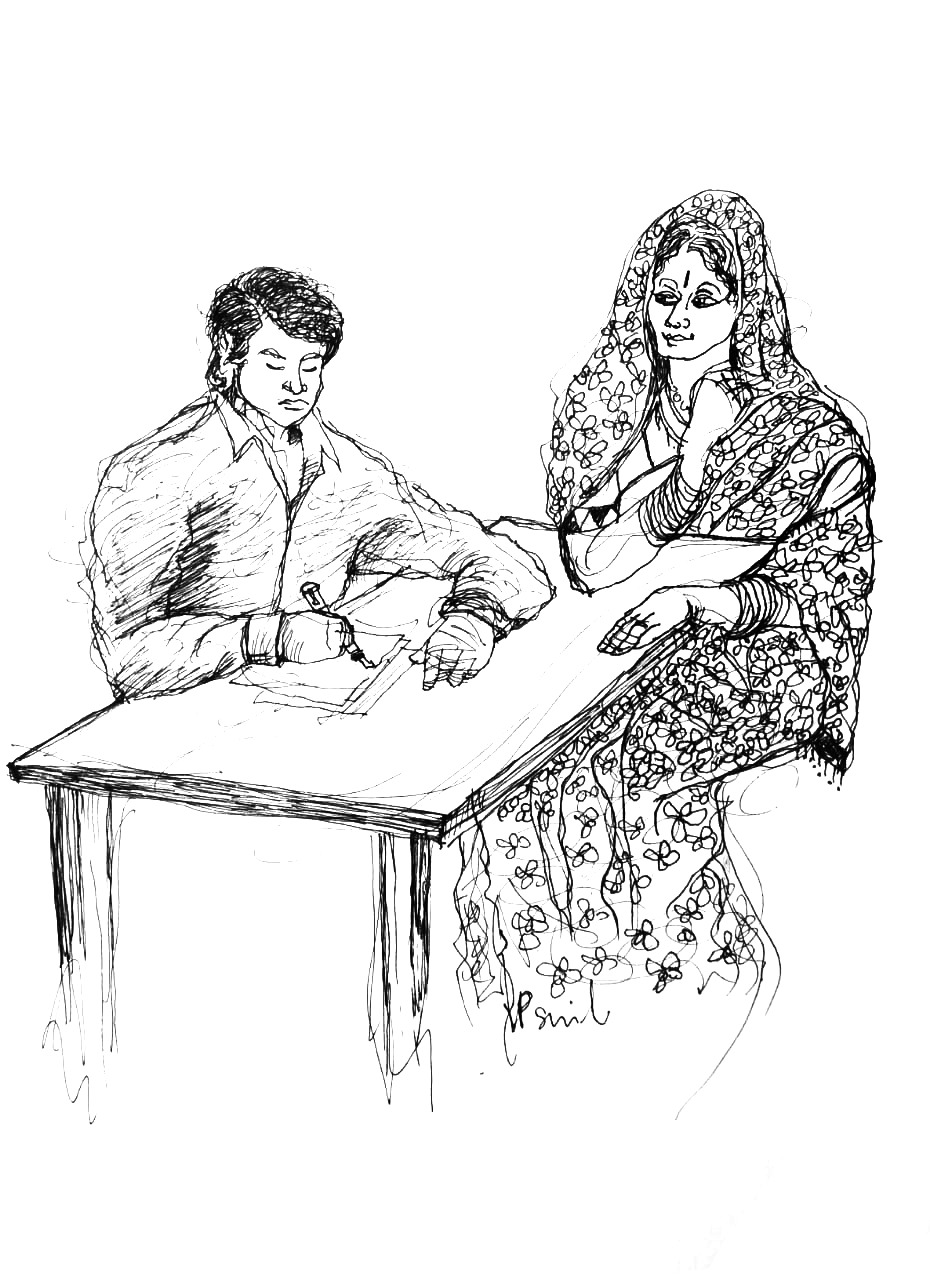

“Minar, you must write a letter for me.” Chandralekha said. She glanced behind as if to make sure that Bharati had gone to kitchen to prepare tea. “I need to send that letter by courier today itself.”

Minar felt as if he heard the murmur of a dove from across the window. He looked at Chandralekha with disbelief. “Letter? In this age of mobiles? You do have a mobile with you, don’t you?” He thought about the young woman who came to him to get her letter written, with no less attraction that he had felt towards her thirty two years back. That was his first day of joining the group of eleven or so of scribes who sat in front of the City General Post Office. They served the illiterate, mainly migrants, by writing their letters for a fee. He was the youngest of the lot. He lived once again through those nice comments and wishes he had received from the other ten scribes. Nizamudin, the eldest of the group feigning surprise said, “Yah, Allah! This first ever letter you write could be a love letter!” Looking at the young woman he asked, “My girl, don’t you like my hand-writing?” She motioned him to keep his mouth shut. “This is between two young minds,” she said. Looking at Minar she asked “Is it your first day on job?” “Yes,” said Minar. “No one so far who got her letter written by you?” she asked again. “No.” said Minar, but added “I write neatly and without mistakes.” She sat near Minar on the wooden box which was doubling as a stool. She looked at all other people who had thronged there like her to get their letters written. She asked Nizamudin, “Chacha, is the number of illiterates in this city coming down or growing?” Nizamudin laughed aloud and said, “No change!”

Minar took a sheaf of lined paper out of the bag and picked two sheets. Getting ready to write, he looked at her. She said to Minar, “Do you know the rule that the other ten scribes here follow?” Minar said he knew. “Wait a moment. Before you tell the rule, you have to tell me your age and name.” Minar said his name first and then age. She laughed. “Minar, 20 years, all right. Now you tell what is that rule?” Minar explained the rule. “Whatever you write down on paper as dictated by those who come here should be kept secret. Never ever share the letter with anyone.” She moved and sat closer to him. “Letter is to my home.” Her smell wafted across Minar’s nose. It smelt like some flower. “Do you know who I am?” She asked. “Whosoever you are” Minar said, “I shall write your letter.” She said, “Chandralekha is my name. You know the red-light street of Kamathipura? I am a woman from there.”

Minar felt that the fragrance which, a moment back, lingered near his nose now spreading down his throat also. Chandralekha said, “My letter therefore should be strictly secret.”

Minar remembered that a horde of doves descended at that time on the tarpaulin which was spread and tightly tied as a tent over the heads of the eleven scribes. And the doves were incessantly cawing. The old post office building standing high in the sun was projecting yet another of its heavy shadow over the tarpaulin, so much so the place suddenly turned so cool.

Those scribes in front of the General Post Office were the custodians of messages sent to their families by their clients, illiterate labourers and Veshyas[1] who made it to the city. Penning letters for this multitude used to be a hectic but paying job, but until the time mobile phones appeared and took over the scene as messengers, changing only the nature of illiteracy and strangely literacy too. On certain days Minar himself used to write forty to fifty letters. Minar sat there writing letters for another thirteen years after mobile phones took over the city. And at last he left. Like all others who were there with him, he also searched for an alternative job. For Minar it was like an inherited occupation- one which was in vogue for centuries. It was Minar’s father who first came in front of the General Post Office in Mumbai to undertake the job which was being called by respectable names like ‘Munshi’ and ‘Khateeb’. He used to tell Minar that he was the Munshi at the Royal Palace. When his father returned to the village home from the city because of old age and illness, Minar came to the city to take up the same job. Other scribes then selected an auspicious day for Minar to start his job. And it was right on the same day, Chandralekha, the young veshya from Kamathipura came to Minar asking him to write down her letter for the first time.

[1] Veshya has an identity which has a different cultural connotation than of a prostitute. The word is not derogatory. The role of Veshya in society has a cultural and sociological context as expounded in Kamasutra by Maharshi Vatsyayana.

Chandralekha showed her mobile phone to Minar. “Minar, I have a mobile with me.” She said, “but what I want to convey needs to be written down, not spoken.” She wanted the letter to be addressed to the college where her daughter studied. “To the Registrar, a copy should be kept for her warden too.” Chandralekha said, “For that I shall take a photocopy.” Chandralekha showed her daughter’s photograph to Minar. Minar asked, “What is her name?” Chandralekha said, “My name itself, Chandralekha.”

Minar stared at her narrowing his eyes. “Why so?” Chandralekha laughed. “Later when she has a daughter she also will be named Chandralekha.” Minar shook his head. “You always drive me crazy!” he said.

“This letter also you must write and keep secret.” Saying “That is my job,” Minar got up and opened the lower drawer of the almirah. He took out pen and paper which was scarcely being used in the present time. Squatting in front of the almirah he said, “It’s been long since I did this job” and while rising up he stumbled once. Instantly Chandralekha rose to her feet and came near to him. Again, Minar took in her smell. Perhaps she noticed it, he felt. He sat on the bed preparing to write the letter for her. He stretched himself across the bed to open the window panes, saying, “Let there be some more light.”

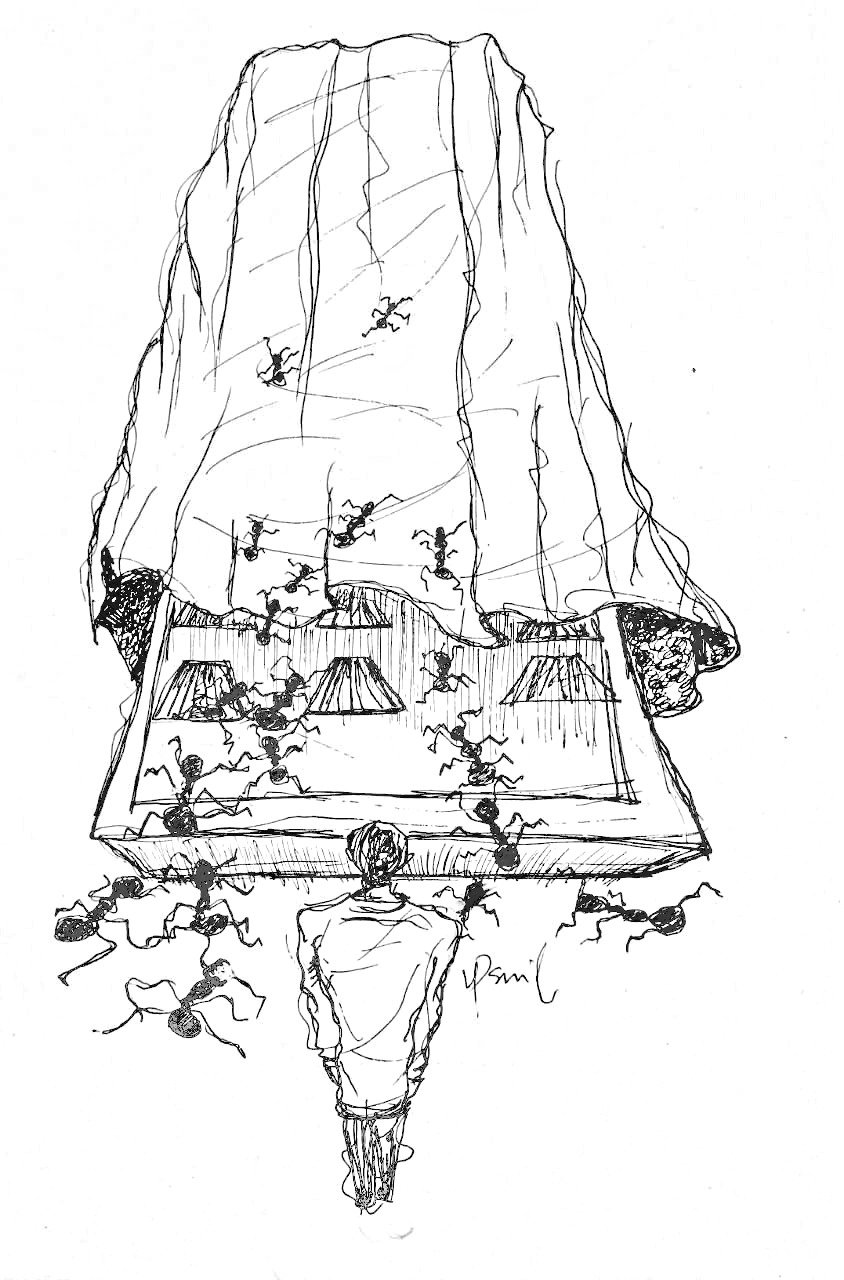

That night Minar had a bad dream. The dream followed him in the days to come. Minar recounted the dream feeling as if the day had started with that dream itself; or as if the day was contaminated with that dream. The dream related to the time when he lived writing letters. In the morning Minar was walking towards the General Post Office. As usual, the road was deserted except for a white cow which he had noticed. But there was a booming noise. First it felt like that of an animal. Then it felt like that of a man. It sounded like a cry. As that sound surrounded him, Minar increased the pace of his walk to a run. He reached in front of the post office building running. But that huge building was completely covered with a white cloth. It was like an enormous box which stood there touching the sky. The noise was produced by ants which were moving up and down the white cloth as if from the floor to a dead-body. As they ran up his leg also by making that horrific noise, Minar woke up startled… Bharati switched on the light. “You had a bad dream?,” Bharati ran her fingers through his hair. She gave him water kept in a jug. Minar searched for the ants first on his feet and then on the bed. His thoughts went to the day when he returned home putting an end to his job as a scribe. He remembered saying Bharati how he felt himself; not so much as an unemployed, but more like the statue of the forgotten hero of the city. He also remembered how he began working as the third security guard in the city’s English school. Even while sitting at the school gate, he had felt that he was sitting there to write down letters for others. Gradually that job too came to an end. “I will blow out the lamp after some time…” Bharati sat close to Minar.

“Whom was Chandralekha’s letter addressed?,” Bharati asked. “To her daughter’s college.” said Minar. “Oh! Her daughter has grown, hasn’t she?” Bharati asked. “Is she in this city?” “No, in Pune.” Minar said. Minar took hold of his wife’s hand and kept it over his chest. He wanted to describe the nightmare to his wife. But he did not. He decided to call his son next morning.

But that was not necessary. Bharati had already asked their son to come home fast.

The next morning as early as at 8 o’clock, two young police men arrived. One of them showed Minar a photocopy of the letter he had written for Chandralekha the previous day. “Did you write this?,” he asked. Minar felt crestfallen that the covenant he adhered to throughout in his professional life was broken. The letter itself has been leaked!

“Do you know to whom you wrote and gave this letter?”

“I know.”

“Who?”

“Chandralekha.”

“Yes, do you know who she is?”

“A woman from Kamathipura.”

“Not woman, a hag, a prostitute.”

Minar did not say anything. The police man, as if to contain his anger, took out a cigarette, kept it between his lips without lighting. Now the second policeman asked, “Since how long you know her?”

“I know her since long, I know her for 30 years.” Minar said.

Second policemen then looked at the first and laughed. He threw a nasty glance at Bharati. “Is she too from there?” he asked. Minar looked at that young man with a shudder.

Bharati smiled looking at the policeman. “I shall prepare tea for two of you.”

The policeman looked down and said “Sorry.”

The first policeman explained that their visit was part of an investigation that they were ordered to carry out and Minar should co-operate. Minar cleared his throat in a bid to restore his voice which was choked so long. He asked his wife to get a tea for him too. Now he felt confident to face these young men.

Minar said: “As you may know by now, I was one among the eleven letter writers who once sat at the main entrance to our General Post Office. For thirty two years I was with that job. We kept the letters of those who came to us as secret. Me too. That was our profession is… ”

Minar uttered the next word in English, for the benefit of the young police men: “Ethics.”

At that time Minar felt the two small ants which he had seen in the nightmare climbing his leg over the heels. Minar shove the ants to the floor.

The second police man laughed looking at Minar. “But our job is to crack such secrets.”, he said.

They remained there for some more time. Then they sipped the tea that Bharati brought and started off taking Minar with them. “Nothing to worry,” the first police man told Bharati. “Let him come to station and meet the inspector also.”

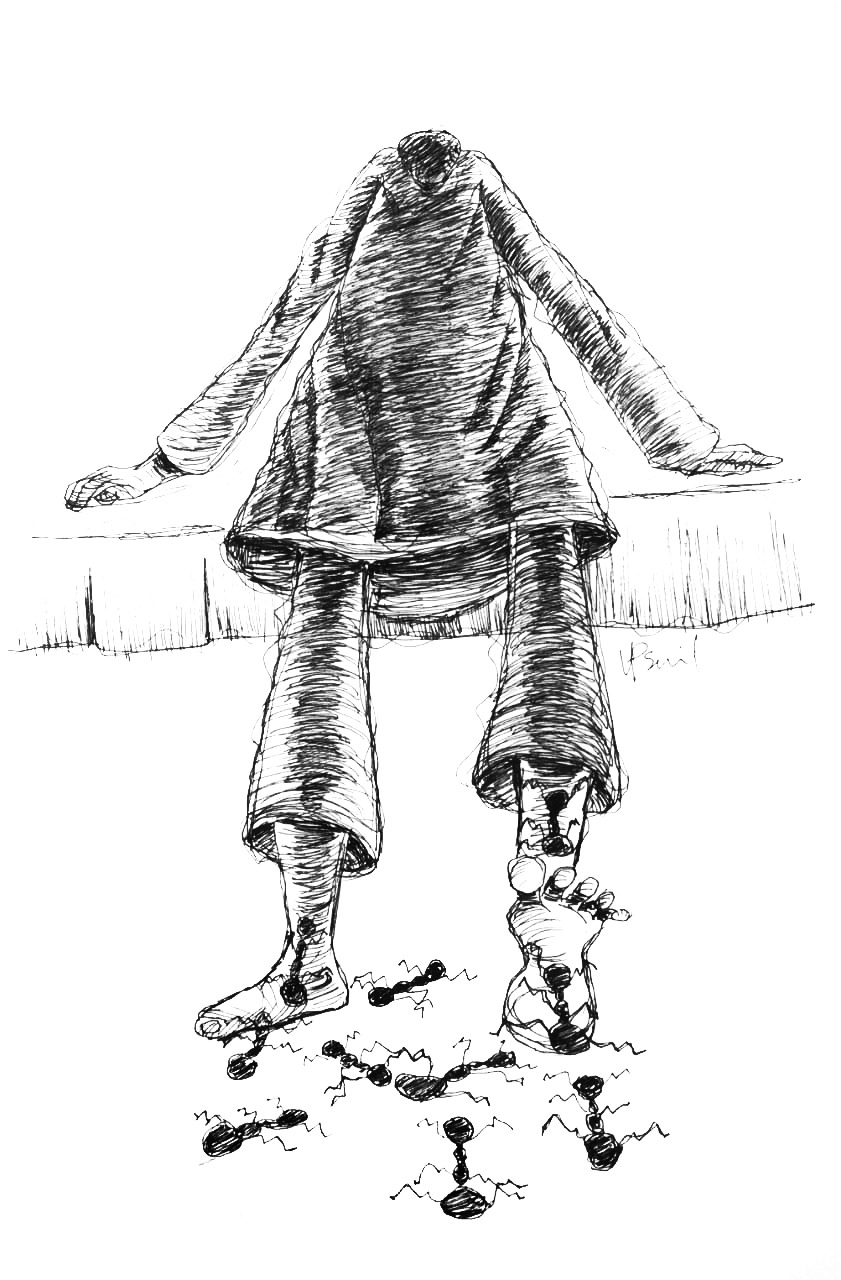

That evening by four o’clock, Vikas, Minar’s son, brought him home on his scooter. Vikas asked, “Are you resuming the job which you had stopped once?” “Baba, do you know the seriousness of the problem you have landed yourself in?” Minar did not show that he heard his son. Actually, he felt like roaming around the entire city. He felt like telling his son, “Look, you leave me in front of the post office. I will come home after a while.” He felt he saw himself in front of the post office writing letters. Minar imagined that the day was unfolding as a continuation of a day which had opened some time in the past. Time is not twenty four hours a day. Certain days are like blocked on the way, while others continue infinitely like a small boat sailing across the sea.

The same day a group of about hundred Veshyas of the town staged a “rasta-roko” in the streets and later surrounded the police station to protest against taking Chandralekha into police custody. Minar tried to go and witness the action, but Vikas stopped him. Instead he made his father sit in front of the television which was showing the entire action outside. The area milling with protesters spread over 233 square feet as captured on TV resembled a gigantic creature pushing and heaving. In the street there were other men and women who joined the women from the red-light streets. Minar searched for Chandralekha in that crowd.

“That hag is not there”, Vikas said. “She is in police custody.”

“Don’t say like that, but refer to her with respect.” Bharati corrected her son. “Learn to respect the elderly.”

Vikas said sorry and corrected himself. “This protest is to get Chandralekha released”, he said. “Baba, this will not end so easily.”

Minar came to the balcony. From out of the shadow in the balcony cast by the retreating sun two doves flew out into the street. Minar stood there for a while following with his eyes the path along which the birds had flown.

Next day morning lying on his cot, Minar tried to recollect the events of the past few days. The procession which passed down the street on the day when Chandralekha came to meet him was in protest against the suicide of a college student in another city, now the current processions are for the sake of a Veshya. Minar wished to meet Chandralekha and he disclosed it to his wife. She agreed to accompany him to the police station, but attached a condition.

Bharati was preparing breakfast in the kitchen. She looked at Minar while mixing egg, green chilies, turmeric and salt in a glass bowl. “But the root cause for all these problems is in the letter you had written for Chandralekha. You must tell me what it was.

“Minar laughed and shook his head in the negative. That is a secret to be kept in that profession.” Bharati stretched her arm and softly beat her husband’s cheek with her palm. “My dear Munshiji! Are you not aware that it is your guarded secret that is being discussed in TV channels across the whole nation?”

The discussions were over the Veshya in the red-light street, her daughter, their religion and caste, ethics and justice. But what triggered the present series of agitations was the letter written by the mother to the Registrar of the University who had insulted her daughter. For the same reason, Minar who had written that letter for the Veshya was summoned to the police station.

“Tell whether what all was in that letter was narrated by her or were on your own?” Inspector asked. He kept the mobile phone on the table to record the questioning.

“This will constitute evidence.”

“No sir, it is her letter.” Minar said.

“Nothing of your own?”

“No, my letters to her voice… it was like that.”

“What? Say that once again.”

Minar had several times run through in his mind the hours of interrogation of that day. Now he felt that each line of that letter had filled his mind like a town which bore in it many a secret.

“Ok. Not necessary. But what is the sentence which is said to have insulted the Registrar?” Bharati again asked her husband.”Say it, if only you want me to accompany you.”

Minar thought that Bharati would be now glancing sideways at him. “That is also a part of the secret.” said Minar. “But, your coming with me will make me happy.”

Again all these spread into several other episodes. Like stories from different streams merging into the main story. That day, as directed by the court, it was decided to remand Chandralekha to police custody for one more week. But, on the way from the court to police station, somebody attacked Chandralekha. Chandralekha and a policeman were admitted to the hospital with serious injuries. City was once again abuzz with protests. A crowd set ablaze a police van. Same time there was a fire in a building in Kamathipura leading to clamping of curfew in the city. Three persons threatened Minar that night over telephone that unless he leaves the city immediately, his house will be set ablaze. “Pimp of a prostitute!” one of them rebuked Minar. Next day early morning Vikas and his wife arrived to take the parents to their house.

Vikas said, “Just that one sentence in the letter is enough for them to set ablaze this whole city.”

Minar looked at his son. But Vikas looked at Bharati only. “I am a Veshya and my daughter is the daughter of a Veshya and therefore her caste is unknown”. Anybody can understand what she wrote, as she is a prostitute.” Minar found that his son’s voice was getting louder.

“Why are you saying all these so loudly now?” Minar asked his son and said, “Don’t be so loud.”

But Vikas looked at his mother only. “Suppose, you were my man that day, I would not have asked your religion or caste. I would only have done everything to enhance your pleasure… ” Vikas now turned to Minar. “This is the dangerous line in that letter.”

Minar asked his son to be calm. “You are unnecessarily making noise.”

Vikas really raised his voice now. “While taking down this sentence Baba, you could have corrected her—that illiterate!”

Bharati’s voice now stopped her son from continuing. “Stop!”, Bharati said. “There is nothing wrong in what Chandralekha said or what Baba took down. Anyone with sense can understand who is at fault. You do not have that sense now. No more such talk here. Baba and I will remain here only. What Baba did for thirty years made you a literate. But it is more difficult to infuse sense than make one literate… We are old now. Today a woman of the same age as your mom was attacked by persons of your age… ”

Minar held Bharati’s hands. Bharati sat in the sofa as if exhausted. Vikas came and sat beside his mother. He grabbed her both palms into his palms and closed them. All remained silent. Minar felt that the room was getting filled with the sorrow of a life time. He walked towards the bedroom.

Minar called her wife to the sitting room in the night when they were alone. He put off the light in the room and opened the windows facing the street. Saying that light was adequate, he switched on the fan.

“May I tell you a secret which I had not shared with you so far?” Minar said. “If again it is the secret of that letter you need not tell.” Bharati said. “Not that,” Minar said. “I had once visited their brothel. That is the secret.” Bharati wanted to hear once again what he said. “May I tell?” But Bharati only looked at her husband instead of saying yes or no. Minar told her about his visit to the red-light street where Chandralekha lived when he was twenty years old. “One time.” “When I asked Chandralekha where she lived she laughed aloud. What all things yet remain for you to know about this city!” She mocked at him. That was her second visit to him during that month.

“It is as one turns twenty that he can discover beautiful women,” said Chandralekha, looking at the letter writer, four years younger to her. “I shall take you to my house one day-as a guest of all the beautiful women there.” Minar looked at her shyly. He breathed her smell once again. And he tried to recount the particular flower which produced that smell. “Just as you keep my letters secret, I will also keep your visit a secret.” But Minar did not accept her invitation in the next two months. But later he did go with her, that too walking along the city streets as she had wished.

That day, as Minar accompanied by Chandralekha reached her house in the red-light street in full day-light, seven young women of her age came down to the street and received them. Uttering, “Chandra’s darling letter-writer!”, one woman took hold of Minar’s hands. They led Chandralekha and Minar along the verandah on the first floor to a room. An uncommon place and a different smell, Minar thought! He also fancied that he would be the sole male in the whole building during that time of the day. Young women draped in colorful dresses passed him. Air laden with different smells trailed after them. A few of those young women gently touched Minar on his cheeks.

A few stroked Minar’s hair. A few held Minar’s hands. Chandralekha blinked her eyes to him as if to reassure to him not to mind these ministrations. She said, “You are our guest.” As they entered the room, there too another group of young women welcomed Minar. Minar decided that he has arrived in a planet which was inhabited by females only. He told Chandralekha that they could now return. “You are getting scared seeing the women, aren’t you?” She made fun of him. She made Minar sit on a cot. She sat beside him. Other ladies stood around them in a circle. Someone asked him his name, age and place. She asked him whether he can disclose the secrets in Chandralekha’s letters. They asked him whom he loved also, whether he would marry the same girl whom he loved. He was also asked whether he had slept with any woman.

A young woman sat at Minar’s feet. She held his feet together and tickled him.

“You have not slept with anyone so far?” she asked.

“No.” Minar said.

The young women in one voice shouted “Hoi.” Chandralekha pushed that woman aside and said to everyone.

“He has decided to remain a letter-writer for a couple of years more.”

Bharati laughed looking at her husband. “My poor letter-writer,” so saying she pulled Minar to her shoulder.

“Then what? Continue, I too feel as if I was there as one among them!”

Minar looked at his wife narrowing his eyes. He felt that they became old too soon. Minar said, “They gave me a souvenir that day.”

“Souvenir?”

The young woman who sat at Minar’s feet stood up and ordered all women there to stand in a row. She pushed Chandralekha away. The women taking one step back stood in a semicircle as if in a dance.

“I am not going to ask you to say whom you want out of us.” She said to Minar, “You are too good. You are going to marry the first girl you meet. But without giving a present, how can we allow you to leave? That too from a brothel? She took out a blue sari which was spread over the window for drying. She smelt it and said “Ha!” Then she draped the sari over Minar’s eyes tying it like a kerchief.

“Only one out of us will present that gift to you. Otherwise somebody not in this group whom you have not seen at all. Do you know why your eyes are being blinded? If you are not made blindfold now, you will remember not the face of the girl you marry but the one who is going to present this gift to you. That should not happen… ”

She tied the sari over Minar’s eyes. She clapped. There was a ringing laughter which flowed out of that room. Its place was taken by a deep silence. Minar was alone in the room. He wished to get up from the cot. At the same instant, a smell which was not there before and which would not be experienced ever again, like the memory of a sacred place, enveloped him. Minar felt that he was going to another world. Perhaps to death itself. Startled, Minar got up from the cot and raised his hands to untie the sari which was blindfolding him. Promptly, two hands with the long lasting sound of bangles prevented him… They held him close from behind.

“Same time that woman kissed me in my mouth for the first time… ”

Bharati embraced her husband stretching her right arm. She kissed him over his cheeks and eyes. Minar had started crying.… But Bharati was not sure whether it was the cry of an old man or a youth. Light from the street was now making the entire room visible. Bharati dried her husband’s eyes. She said, “Don’t cry. Let us wait for the dawn”, she told him twice or thrice. Minar said he wanted to sleep… He walked to the bedroom with his wife. He stumbled once on his way…

Translated from the original in Malayalam by E. Madhavan, CHIRAG, KLRA 46, Kannath 3rd Sublane, (P.O) Ayyanthole, Thrissur 680 003., Kerala.

Karunakaran is a story writer, novelist, poet and a playwright. His stories include ‘Makarathil Paranjathu’ (Stories – Patabhedam), ‘Kochiyile Nalla Sthree’ (Stories – Sign Books), ‘Paayakkappal’ (Stories – D. C. Books), ‘Ekaanthathaye Kurichu Paranju Kettittalle Ulloo’ (Stories – D. C. Books), ‘Athikupithanaya Kuttanweshakanum Mattu Kathakalum’ (Stories – D. C. Books), ‘Parasyajeevitham’ (Novel – D. C. Books), ‘Bicycle Thief’ (Novel – Mathrubhumi Books), ‘Yuddakaalathe Nunakalum Marakkombile Kaakkayum’ (Novel – D. C. Books), ‘Yuvavayirunna Onpathu Varsham’ (Novel – D. C. Books), ‘Yakshiyum Cycle Yathrakkaranum’ (Poem – Green Books), ‘Udal Enna Moham’ (Articles – Logo Books). He is a recipient of O. V. Vijayan Literary Award instituted by Hyderabad Naveena Samskarika Kala Kendram. Karunakaran is working in a private firm in Kuwait.

E. Madhavan was born to Malayalam poet Edasseri Govindan Nair and E Janaki Amma in Ponani in Malappuram district, Kerala on 9th November 1950. After graduation he went to New Delhi as a job seeker. After undertaking short assignments as tuition teacher and assistant in a textile research laboratory, he joined the Reserve Bank in September 1973 and served in all the four major cities apart from Thiruvananthapuram and Kochi. Post-retirement he has been acting as Secretary of the Edasseri Smaraka Samithi while pursuing his interest in literary translations, financial literacy etc.

Wife: Susheela.

Daughter: Sreedevi.

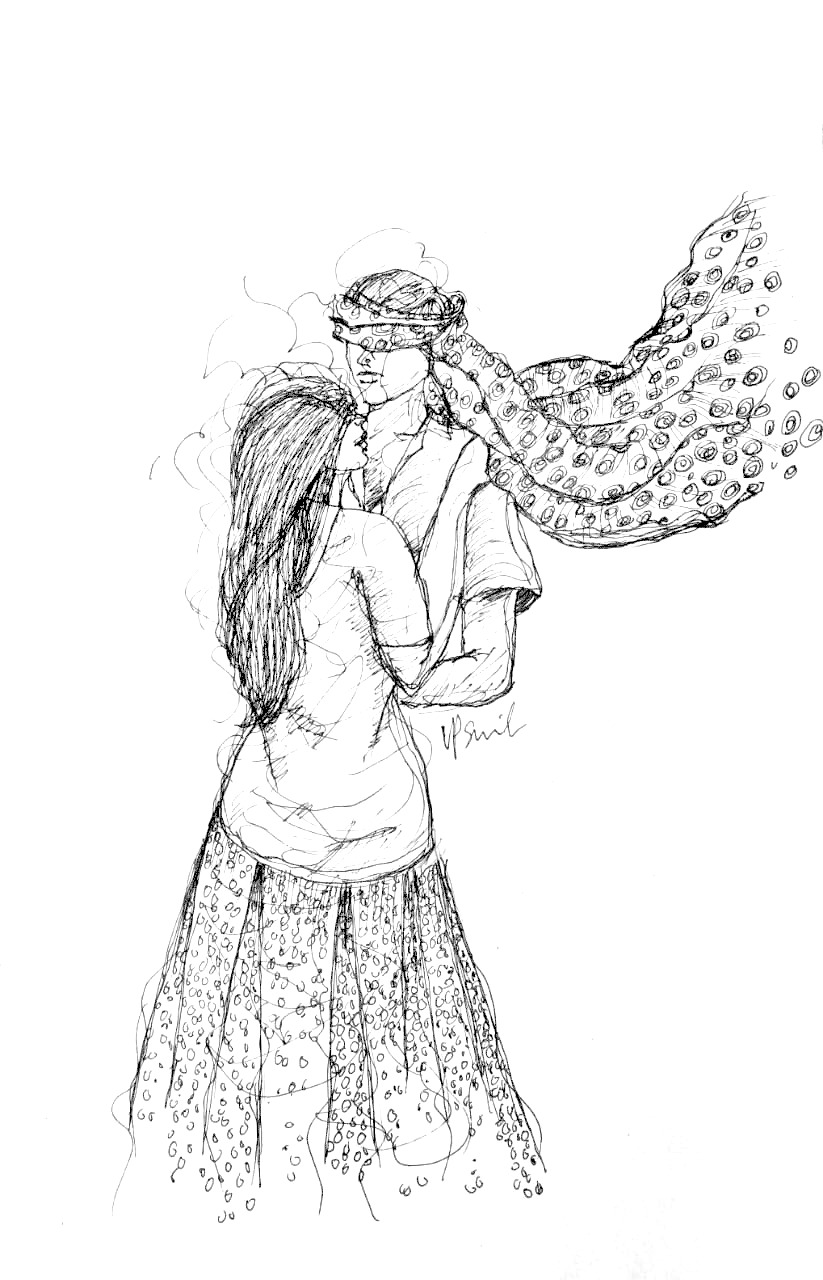

Illustration: V. P. Sunil Kumar